Those thinking that the turning of the year would immediately bring better news now know that they will need to wait longer. January was again not a happy month for investors. The US share market had its worst beginning ever for the first 20 days. The early-month weakness was concentrated in financials rather than in cyclical stocks, suggesting that the ongoing banking sector problems were of more concern than the general economic weakness. For all of January, the S&P500 index fell by 8.6%, although it remains 9.8% above its 20 November low. Here in Australia, the ASX200 index hit a new low for this episode on 23 January, and dropped 4.6% in the month, making January the twelfth negative month in the past fifteen.

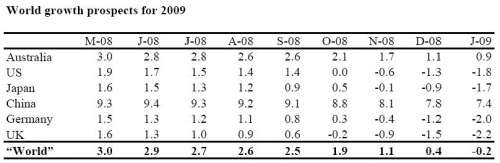

The economic news also continues bleak. Growth prospects around the world continue to fall. The evolution of the so-called consensus forecasts for the major economies in recent months is shown in the following table.

Source: Consensus Economics Every number in this table is a forecast for GDP (or economic output) growth in 2009. The column heads refer to the month in which the forecast is made. If one looks along the lines (and any line will do) the picture is remarkably consistent. Through to September last year, growth forecasts were trimmed month by month. Since September they have fallen off a cliff. I cannot recall any time when economic prospects have changed so quickly. I have a very simple model in my head; so simple that it could be called childish. Share markets are forward-looking. When the outlook for economic growth is improving, markets will tend to do well, and when the outlook is worsening markets will struggle. This very simple model has worked amazingly well for almost six years. From early 2003 until mid-2007, forecasters did nothing but raise their growth forecasts, and equity markets thrived. Since mid-2007, forecasts were shaved and markets subsided. In the past four months, both the economic outlook and the value of markets have plummeted. But here’s the point: in the not-too-distant future the bottom line in this table will stop falling, and start to creep back up. The economic scene will still be grim, but markets can begin to price in a "perhaps not as bad as previously thought" future. Bear markets always do end, and the average gain in the Australian market in the next 12 months has been 38% (since 1970). Of course, we may not be at the turning point yet, although shares are now so cheap by any conventional measure that we may well be. The Economic News Bleak bleak bleak. For some time last year it was fashionable to argue that Australia would avoid recession, in part because we had the ability to loosen both monetary and fiscal policy, and in part because China would save us. The latter was always going to be wrong—China has slowed alarmingly, and is now itself in recession, along with almost of the developed world. Right now, Chinese production is falling. It’s important to note, however, that this is a cyclical thing; China still has decades of super-normal growth in its future. I was as guilty as the next economist in thinking we could avoid recession. Instead, it’s turning out like Nevil Shute’s This doesn’t mean that the policy-makers have failed. Business cycles are inevitable in a capitalist economy, and particularly in one that is so hostage to what happens in the rest of the world. Rather than bemoan the recession, we should applaud the fact that we went for seventeen years without one (and if the next one is seventeen years away, I won’t be writing about it!). Of course, the policy-makers have tried. The RBA has eased more aggressively than ever before, and the Feds have been on the job with fiscal and "interventionist" measures. The recent fiscal package has been derided by many as a waste because its effects were only temporary. Even if b were true then a wouldn’t necessarily follow! And some of the interventionist measures smack of "policy-making on the run", but that has been true all over the world in recent months. We’re somewhere we’ve never been before, and the policy-makers are entitled to a mistake or two as they try to figure out what helps and what doesn’t. I’m sure that you all recall Act 5, Scene 2 of Hamlet, when the prince opines: "there’s a divinity that shapes our ends, Rough-hew them how we will" Economic policy has been rough-hewing in Australia, but it hasn’t been able to avert recession. Although there may be little operational difference, we need to stop pretending that we can prevent a recession, and instead set policy to maximize the chances of a solid, sustainable recovery. Many fear that the extraordinary measures taken abroad have so pumped up the money supply that inflation will return with a vengeance. Not a chance. In modern economies, you can’t have an outbreak of inflation with activity so depressed, and it will be that way for a long time. One thing that will need to be addressed in the medium term is the shape and nature of financial systems. Will we live for a long time with governments big players (because they are part-owners) in the global financial sector? If we do, what are the implications of this for innovation, productivity growth etc? What will be the optimal degree of regulation in the future? These are very difficult issues; I’m glad that it’s not my day job to sort them out. But the answers arrived at will make a huge difference to how economies function in the long run, a vital concern for investors. Chris Caton Chief Economist BT Financial Group Disclaimer and Disclosure This publication has been prepared and issued by BT Financial Group Limited ACN 002916458. While the information contained in this document has been prepared with all reasonable care no responsibility or liability is accepted for any errors or omissions or misstatement however caused. All forecasts and estimates are based on certain assumptions which may change. If those assumptions change, our forecasts and estimates may also change.